Education is as old as humanity. Since the beginning of time, I believe we have been trying to teach each other. We’ve been trying to learn together to understand our surroundings, to be safe, to try cool things, and to encounter the inescapable qualities of mystery.

Somewhere in one of the authoritarian eras, our initial and naturally curious dispositions were channeled into learning much more mechanically and much less holistically. Learning shifted into transactional exchange, with unusual attention to the parts rather than the whole.

Phew! I realize I’m pulling out a rather big and spotty narrative here — stay with me.

The industrial era, for example, radically changed the nature of craftsmanship. Capitalism brought speed and efficiency. So did the arrival of the factory. It also collapsed a pile of artisanry. What once was responsibility to make the whole shoe became scores of people that only mass produced the heels, or the tongues, or the eyeholes for laces.

Authoritarian eras highlight power and transaction. One person knows something and must teach to others, who are generally expected to absorb the expertise and then replicate it. You can feel the partial truth in this, right? Of course it is important to learn. Of course it is important to learn from people who know how to do things.

However, I’m a bit disappointed with the limits of the expert model and what that does to communities trying to engage — these days. I feel myself and many others trying to rework, and reclaim alternative stories that bring greater vitality among all of us learning, and the temporary spots we hold of teaching.

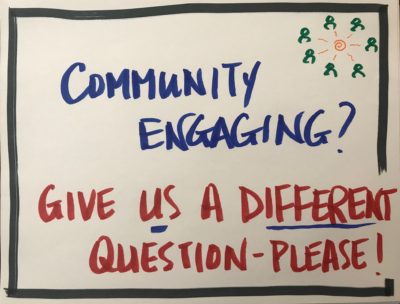

Let me pull this down a bit to more specific contemporary example. A couple of weeks ago I was participating in an online class. The format is one hour long. There is good material that the teacher shares. This is a small class — there are 8-10 of us. After going through the material, the teacher asks, “Do you have any questions?” It seems like a good question. It seems kind. There are times when this is just the right question. However, in that moment, and I believe most moments like this, that question intended to invite added learning actually shuts learning down. People clam up. There’s quite a silence. And as often seems to be in those circumstances, it’s only an obligatory kind question that someone asks just to remove the silence, but has very little meaning.

To be fair, I’ve asked that kind of question before. Sometimes with success. Sometimes with similar weird silence. These days, I grumble a lot inside. What takes this from teacher / class to a community / engaged is rather simple. One, invite all to speak to a slightly different, yet significantly altered question — “Is there a learning or question that this stirs up in you?” Notice that this question presupposes a bit more room for the unresolvedness that lives in questions. It’s not a report. It’s not a test. It’s an invitation to deposit your transparency to the good of the group. The other simple thing, two, particularly if the group is too large or the time is too short, is to make smaller groups. Again, have each person in the smaller groups respond to the modified question — “Is there a learning or question that this stirs up in you?”

What comes from this shift in question is, one, much more participation. And, now back to the bigger sweeping story, creating more participation and engagement is the reclaimed modality here. Less “I’m the jug; you are the mug.” Way too old of a disposition. More “There is wisdom in the group that will only come about through some designated and deliberate interaction.”

This post feels like a bit of a rant. It is, I suppose. I feel a bit whiny in writing it. Yet, I also feel a bit aware that interrupting patterns, including the primary assumptions about interaction, is some of the most paramount work of our times. The renewed story these days — I’m glad for those in it — is to help animate more aliveness in everyone connected to the issue, or the problem, or the opportunity, or the wondering.

Let’s wrap this one up for today. I’ll offer a premise that rests behind most of the work I do that has direct implication on nuancing questions and working in any group settings. This is the most simple I can find for me. It’s the most honest I can find. And, well, thankfully, it’s quite fruitful (again when indicator of fruitfulness is about witnessing people and groups come alive). Ready?

There is always more unseen than seen.

There is always more unknown that known.

This alone changes how we are together.

Now let me quote again Margaret Wheatley, friend and colleague from these many years. On the back cover of her book, Turning to One Another she offers this:

There is no greater power than a community discovering what it cares about.

Ask “What’s possible?” not “What’s wrong?” Keep asking.

Notice what you care about.

Assume that many others share your dreams.

Be brave enough to start a conversation that matters.

Talk to people you know.

Talk to people you don’t know.

Talk to people you never talk to.

Be intrigued by the differences you hear.

Expect to be surprised.

Treasure curiosity more than certainty.

Invite in everybody who cares to work on what’s possible.

Acknowledge that everyone is an expert in something.

Know that creative solutions come from new connections.

Remember, you don’t fear people who’s story you know.

Real listening always brings people closer together.

Trust that meaningful conversations change your world.

Rely on human goodness. Stay together.

I believe we are living in an era that seeks so necessarily to reclaim aliveness with one another. The tools to get to that are not particularly complicated. But they are a practice, and ongoing practice. They point us to encountering one another, and trust that there is some of the mystery that we will find together, and in the moment, that will carry us to another part of the mystery. It’s rather simple, but oddly, changes the whole picture, just like a slight adjustment does in viewing a kaleidoscope. The shift in the questions we ask, and the assumptions behind it, I think move us, thankfully from old strictarian teaching to animated community, which I’m guessing, is where education has been wanting to return to for a long time.